Coventry Cathedral has a fine peal of twelve bells (plus two semitones) cast by Gillett and Johnston in 1927 but not hung for ringing until 1986 because of structural problems with the tower. Coventry Cathedral was completely destroyed in an air raid on the night of 14/15 November 1940, apart from the tower, but the bells hung for chiming high in the tower were unharmed. Prior to the casting and installation of these bells, Coventry had a peal of ten which were by reputation one of the finest rings of their age. They were originally cast by Pack and Chapman in 1774, though the 6th was recast by them in 1799, and the tenor by Briant in 1804 after it was cracked in 1802. When the old bells were taken out for recasting by Gillett and Johnston in 1926, they were the subject of a famous court case. The long and interesting history of the bells at Coventry is covered in Chris Pickford’s ‘The Steeple, Bells, and Ringers of Coventry Cathedral’, privately published in 1987, and the court case is covered in ‘Coventry Bells and how they were lost’, E. Alexander Young, 1928. At the time of the case, the bells had not been rung since 1885 because of structural problems with the tower, and the sound of them in changes was already a distant memory.

Details of the bells, and what I believe is an authoritative recreation of their sound, can be found on another page.

The account of the court case included in Young’s book is transcribed below, together with an editorial which appeared in ‘The Ringing World’ following the case. The book also includes a report on the old bells by A. A. Hughes of the Whitechapel Bellfoundry included on another page on this site. The remainder of the book comprises correspondence showing how Alexander Young mobilised such forces from the ringers of England as were prepared to help him fight the faculty for the recasting of the bells.

There were several issues at stake in the Coventry case. Though much of the evidence and discussion in the Consistory Court was about the relative merits of true-harmonic (aka ‘Simpson’) and old-style tuning, there was also a strong wish to keep ringing bells rather than a carillon at Coventry in the hope that they could eventually be hung for full circle ringing. Also, at the time, Taylors and Gillett and Johnston had both been casting true-harmonic bells for several years, putting the Whitechapel Bellfoundry, who were still casting old-style bells, under commercial pressure. A. A. (Bert) Hughes, proprietor of Whitechapel, called as an expert witness in the case, was clearly torn between his wish to preserve a historic peal of bells, and the commercial realities of the competition from Taylors and Gillett and Johnston.

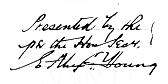

The copy of Young’s book in the British Library from which this court account was transcribed was signed by him as Secretary of the Central Council of Church Bell Ringers and publisher of the book:

COVENTRY BELLS ENQUIRY

Reprints from “The Ringing World,” January 15th and 22nd, 1926

FACULTY FOR RECASTING GRANTED

The petition by the Vicar and churchwardens of the Cathedral Church of St. Michael, Coventry, for the recasting of their bells was heard on Monday, the 4th inst., and, as already indicated by the summary of the proceedings which appeared in our last issue, was granted.

The Chancellor of the Diocese (Mr. E. W. Hansell) held his Consistory Court in the ancient buildings of the Palace Yard, Coventry, and the case occupied over four hours. Sir Henry Maddocks, K.C. (instructed by Mr. W. P. Legender), appeared for the Vicar and churchwardens, and Alderman J. S. Pritchett, Recorder of Lincoln (instructed by Messrs. Rotherham and Co.), was for Mr. R. Caldicott, who opposed the petition. The Apparitor-General (Mr. G. J. Dalton) having opened the court, Mr. Walter Brewitt, the Diocesan Registrar, declared the terms of the application.

After the usual preliminary statement on either side, Sir H. Maddocks opened the case for the petitioners. He said the original proposal to melt down the ten bells into 14 had been amended, as stated, and the present scheme was unanimously approved by the Parochial Church Council on June 17th last. He said that the inscriptions upon the present bells would be again used. He outlined the history of the bells from the 15th century, and said the peal was recast in 1774, and subsequently two others (6th and 10th) in 1799 and 1804 (the tenor for the third time in its history). They were thus not ancient bells in the ordinary sense of the term. The present bells were not harmonious, the first seven bells were each a quarter-tone flat, the eighth and ninth were 1-8-tone flat, and when they came to the tenor, that was not in tune with itself, the hum note being an augmented seventh (nearly a tone within the octave). He was told that these bells were cast at the worst period of bell founding in history, and that was why they were so discordant, and not in harmony with themselves. It was only recently that the great secret of the harmony of bells had been rediscovered. This was known as the Simpson or five-tone principle, and it was this principle which it was proposed to adopt, so as to obtain the best results. He added that it was proposed to recast the ten bells as they were, with headstocks provided, so that they could be rung in the English manner if ever fortune gave them some place strong enough to allow them to be rung. It was proposed to add two bells to match the ten bells, so that there would be a ringing peal of twelve bells; and two other bells would be added for carillon purposes.PIANO DEMONSTRATIONS

Dr. W. H. Brazil, B.Sc., was then called, and gave particulars of the defects which he had found in the bell tones (as previously enumerated by counsel). He explained the tones of a bell, viz., fundamental, hum and nominal, with certain overtones or harmonics, i.e., the tierce (or Minor-third) and quint (or Major-fifth), illustrating them severally on a piano. All the bells in the peal, he said, were distinctly out of tune, their harmonics all wrong, and in most cases the hum note nearly a full tone sharp. The bells were horribly inharmonious, and indeed belonged to the very worst period of English bell-founding, the last half of the 18th century and first half of the 19th. Dr. Brazil then proceeded to explain the Simpson five-tone principle, and demonstrate its tones by chords on the piano, and also those of the old-style tuning, the one sounding harmonious and the other very discordant. (The notes were (1) C, C, E flat, G, C, and (2) C sharp, C, E, G, C). The new bells would be fitted with headstocks, so that if, at Coventry, they ever had a tower, they might be rung.

Cross examined by Mr Pritchett, he said he had made a special study of bells. He had musical taste and a good ear, and could judge one-eighth of a tone. His statements were not merely conjecture, nor his illustrations upon the piano misleading.

Upon being asked if he was aware that the bells of Coventry had always had the reputation of being the finest peal in England, he replied: ‘I have heard so, but do not agree with it.’ He admitted, however, that he had not heard them rung, as they had not been rung for 40 years. He had heard them chimed. He denied that when bells are rung in peal in the English fashion, the harmonics are merged into one sound. Asked if he knew that for centuries they had been regarded as one of the finest peals, he said that he had heard so, but the opinion only came from ringers, who were not to be relied on; they cared much more for the ‘go’ of a bell than for its tone. He wished the bells to be the very best and perfect of their kind. Asked which he considered a perfect peal, he replied, ‘Manchester Cathedral is a perfect Simpson peal.’

Answering the Chancellor, the witness said these bells had been recast on the Simpson principle, a system universally adopted by all modern bell founders with such success that we had been able to export £500,000 worth during the last few years.

Mr. Pritchett then asked the witness if he had heard that Mr. Young, on behalf of the church bell ringers, had offered to purchase the bells at price the founders had allowed them for old metal, with a view to their being stored, and later rehung in Coventry, or failing that, elsewhere?

Dr. Brazil: I have heard of it.

Mr. Pritchett: Was the offer considered by the Parochial Council?

Dr. Brazil: It was not.

Mr. Pritchett: What do you say to such an offer yourself?

Dr. Brazil: I should certainly decline it.

Mr. Pritchett: On what grounds? There would be no pecuniary loss, for you would get the price of the metal.

Dr. Brazil: It seems to me unnecessary.

The Chancellor said it would mean getting a faculty, and it was difficult to get a faculty to sell church property.

Mr. Pritchett: You know that the bells are going to the foundry to be melted down?

Dr. Brazil: Yes, but we shall have the same metal back.RINGERS NOT GOOD JUDGES

Dr. William Wooding Starmer, Professor of Campanology at Birmingham University, said he was a writer of articles upon bells. He had examined the Cathedral bells, and found the hum-tones irregular. He agreed with Dr. Brazil’s evidence, but he preferred to concentrate upon three notes in a bell, viz., the nominal, strike and hum. These three settled everything. The hum-notes of these bells ranged from the sixth to the seventh, and this tone was so adopted he thought by English bell tuners in view of change ringing. All the bells varied, and even one bell out made the rest inaccurate. As regards the Simpson principle, it was not a new one. It had been carried out by the greatest of Belgian founders of all time. He instanced the Hemonys, the Aerschodts, etc. The system would improve St. Michael’s bells. He had spent 30 years analysing bells all over Europe.

Cross-examined by Mr. Pritchett, witness said he was, as a boy, a ringer, but had never rung a peal he was glad to say. He could not agree that ringers were good judges of bell tones; they thought more of the ‘go’ of a bell. Asked as to his knowledge of practical bell tuning, he said he was afraid that his knowledge did not lie that way. He admitted that defects were common in bells, and modern ones must be adjusted after casting.

Mr. Pritchett: Have you heard these bells?

Dr. Starmer: Yes, I heard the hour bell this morning, and the hum-note was not correct.

Mr. Pritchett: Would the man in the street find any defect in the hum-note.

Dr. Starmer: Not unless he was a musical man.

In reply to further questions, witness said it was possible to make the bells as proposed, scientifically adjusted and accurate. The citizens might not hear the Minor third, nor could ringers judge the tone of bells. Possibly bells might be too much tuned.

Mr. Pritchett: When these bells are adjusted would they be any better to the man in the street?

Dr. Starmer: I am not concerned with the man in the street, it is whether it is good.

Mr. Pritchett: Do you think, supposing the fundamental note is correct, that it matters one farthing to the citizens of Coventry?

Dr. Starmer: I cannot answer for the citizens of Coventry; one thing is good and the other is not.

In re-examination, Dr. Starmer stated that if the bells were recast there would be more tone and resonance.

Mr. R. Ashton Houseman said he was the secretary of Messrs. Gillett and Johnston, makers of bells and carillons, of Croydon. He had examined the bells, but was not a musical expert. His experience was that recasting always improved the tones of bells, and would effect a great improvement in these ten.

Cross-examined by Mr. Pritchett: He said he had never read or heard of ‘Shipway.’ He was not concerned with the technical side of the business, but with the administrative side only. Their experience showed that these bells are inharmonious, and when contrasted with a Simpson-tuned peal, very bad, the defects being marked indeed.

By the Chancellor: The defects would be more apparent in chiming than in ringing.

This concluded the evidence for the petitioners.CASE FOR THE OPPOSITION

Mr. Pritchett, in opening his case for the opposition, said that though he appeared nominally for Mr. Caldicott, he practically represented the ringers of England, and he was supported by the Central Council of Church Bell Ringers. Coventry bells had the reputation of being an extraordinarily fine peal, and consequently the Exercise took the greatest interest in them, and were loath to have the bells melted on any pretext whatever. He was proud to be one of the four present who had rung on the bells over 40 years ago. He would call these witnesses to testify as to the excellent quality of the bells as a peal. If the peal was first and foremost as this peal was, surely it ought to be preserved, and the citizens of Coventry ought not to be deprived of a heritage, simply because certain experts said the harmonics were defective. It might be possible, theoretically, by recasting these bells to produce a more perfect peal, but he submitted that it was not at all necessary. With the exception of the light ring at Stoke, Coventry had no bells which could be rung to-day, in the old English fashion, on occasions of public rejoicings. As far as bell ringing was concerned, the city would be isolated from the rest of England.

The Chancellor: It is now.

Mr. Pritchett: Yes, but if this petition is granted, all hope of having a ringing peal will be taken away.

Mr. Pritchett concluded by stating that the ringers of England desired this matter to be thoroughly investigated ere the identity of such a famous peal should be destroyed, nor could such a desire be wondered at, considering that as a peal the bells were simply excellent.

After the luncheon interval Mr. Pritchett called Mr. R. Caldicott, a churchwarden of Coventry until last year. He had entered a caveat, he said, on the ground that he thought the scheme had not been properly thought out. He was also influenced by the fact of finding that the bell ringers of England were against it, and because of the more than ordinary reputation of the peal. He had never heard any citizen raise any objection to the present bells.

Sir Henry Maddocks, in cross-examination, asked if he still objected, now that he was to have the ten bells kept as such, but improved, to which witness replied that he objected to the bells losing their individuality. He could not accept the suggestion that they would be better.

Sir Henry: But you have heard the guarantee of the bellfounders?

Mr.Caldicott: Yes, but I beg to differ.

The Chancellor: By previous recasting the bells have already lost their original identity, and have not preserved their original form, why would they lose their identity by recasting in 1926?

Mr. Caldicott replied that he considered the old way better than the modern upon which they were to be recast. Replying further to the Chancellor, he said he was ‘non-musical.’

The Chancellor: To the non-musical they are not out of tune? – Mr. Caldicott: No (laughter). If, however, you get five so-called musical people to say the bells are out of tune, no two will point out the same faults.

WELL KNOWN RINGERS GIVE EVIDENCE

Mr. A. A. Hughes, of the Whitechapel Foundry, London, next gave evidence. He said that his firm was responsible for casting the present bells in 1774. He had made a great study of bells and their tones, going back over a long period. He certainly did not agree that these bells were cast at the worst period, so much depended on the founders. As a matter of fact the 18th century was better than the 17th.

Asked by the Chancellor as to what was the worst period, he replied that the first half of the last century was.

In further examination he said that at the same period they had cast three very similar peals to the one in question, viz., Stepney, Rotherham and Wakefield, all considered good peals; but he thought Coventry still better, and undoubtedly a very fine peal.

The Chancellor: Your firm has cast a number of peals of different kinds?

Mr.Hughes: Yes, we have cast many hundreds of peals, some vary, certain peals stand out, and have always done so. He had always heard Coventry bells well spoken of.

Further evidence was then given as to the history of the bells, and Mr. Hughes was examined as to his report. He said he had recently inspected the bells, and closely checked their ‘tap-tones’ with the aid of specially tested forks. He certainly could not agree with Drs. Brazil and Starmer. As an old peal the bells were remarkably in tune. He pointed out that only the 9th had any appreciable error, viz., 0.15 of a tone, or 5 1/4 vibrations per second out in a total of 308. So much for the main tones. He then described the ‘hum-notes.’ These were not based upon the octave, but varied from a seventh to an augmented seventh. As regards the ‘fundamentals,’ the faults were quite negligible, and as to the ‘hum-notes,’ they could, if it were desired to bring them into accord with present foundry practice, be readily adjusted by the modern tuning machine.

Asked what he would propose, he said it would be better to have the four new bells cast to agree with the old ten, that was, cast upon the old lines with a flat seventh ‘hum-note.’ In further reply, he said that he thought that the latter had been adopted because in change ringing it was more pleasing to the ear. Nothing useful would be effected by the proposed recasting.

The Chancellor: Would there be an improvement if the peal were recast for chiming purposes only?

Mr.Hughes: Some improvement might be noticed by those with very musical ears.

The Chancellor: Would it not be noticed by the great majority of people?

Mr. Hughes: I cannot say, my experience is (and I have spoken to many on the subject) that most people are quite surprised when I tell them that there is more than one note in a bell.Sir Henry Maddocks (cross-examining): Then, Mr. Hughes, we may now take it that there are two kinds of peals, one in perfect tune suitable for weddings, and the other out of tune, to ring for funerals? (laughter.) At any rate, you will agree that the peal would sound better if the defects which you have enumerated were removed?

Mr. Hughes: Undoubtedly.

Sir Henry: And still better if improved on the five-tone principle?

Mr. Hughes: That is a matter of opinion. Some people object to bells being tuned on the ‘Simpson’ principle.

The Chancellor: And some people object to bells being tuned at all (laughter).

The Chancellor followed his remark by a series of questions as to bell-tones, and also as to modern practice in the various foundries. – In replying, Mr. Hughes said that the present day founders cast a large number of ‘Simpson’ tuned bells, and they had at Whitechapel cast many such. His experience was, however, that whilst many might prefer one style, there were, on the other hand, many who preferred the other. He found himself that, as regards tone, a flat seventh gave a certain quality of tone or character to a bell. The ‘Simpson’ principle had now, however, become generally adopted.

Sir Henry: What objection can you urge against the ‘Simpson’ tuning?

Mr. Hughes: My objection, especially in the case of very heavy bells such as we have here, is that the harmonic overtones are very greatly accentuated, producing a howl which is very disagreeable to many people.

The Chancellor: If you were asked to produce again such a peal of bells from your foundry, I take it, then, that you would cast them in the same manner?

Mr. Hughes: Yes, but with the ‘hum-notes’ adjusted to a more uniform pitch.OLD BELLS NOT FOR SALE

Mr. E. A. Young, district surveyor for Lewisham, in giving evidence, said that he had been a ringer for some 35 years. He was the present secretary of the Central Council of Church Bell Ringers, which represented the Ringing Guilds throughout the country. It represented some 10,000 ringers, but it was impossible to give the exact figures. There were, however, 140 delegates who were sent by the Guilds. On the instructions of the President and the Standing Committee, he had, last June and since, taken whatever steps he could to save the Coventry bells. As a ringer he had always understood that these bells stood foremost among the bells of England, and as Secretary of the Council he desired, on its behalf, to heartily deprecate the proposed destruction of them. He supported the caveat entered by Mr. Caldicatt.

Mr. Pritchett: Do you know Shipway’s book?

Mr. Young: Yes, it was published in 1816.

Mr. Pritchett: Does it contain a list of bell towers?

Mr. Young: Yes, and it quotes Coventry amongst the famous peals.

Sir Henry Maddocks, intervening, said he objected to the evidence, and eventually the Chancellor said: I think we can all agree that Coventry’s bells are famous, and we will do our best to preserve them.

In further examination, Mr. Young said that he had made a study of bell-tones, had a musical ear, and did not agree with ‘Simpson’ tuning. He considered it wrong to melt down these bells.

Mr. Pritchett: Did you, last June, on behalf of the ringers of England, offer to guarantee the purchase of these bells?

Mr. Young: Yes, my object being to store them for Coventry until in better times the proposed campanile should have been built.

Sir Henry Maddocks, cross-examining: You have heard all the experts’ evidence today, that these bells would be considerably improved by recasting and retuning. Do you disagree with it?

Witness: I do.

Sir Henry: What, entirely? – Yes.

Sir Henry: But your own Mr. Hughes says they can be improved, do you disagree with him too?

Mr. Young: Yes, I say let well alone.

Sir Henry, proceeding to put questions as to the chords by which tones had been demonstrated on the piano, Mr. Young admitted that the one was harmonious and the other discordant.

Sir Henry: Then you admit that our bells are discordant!

Mr. Young: I admit nothing of the kind, what I say is that it is futile to attempt to demonstrate such tones upon a piano.

A bell is a musical instrument, he added, but of a totally different kind; it has very indeterminate tones, as to the theory of which it was desirable that they should know far more than they did at present. He further elaborated this, and said that he considered it wrong for the ‘Simpsonians’ to attempt to push their theory by piano demonstrations as they often did.

Replying to the Chancellor, Mr. Young said that he was convinced that our bell founders in the 17th century definitely adopted the flat seventh ‘hum-note’ from sheer knowledge that it was an improvement, consequently the ‘Simpson’ reversion was wrong.

The Chancellor: Why was the flat seventh adopted?

Mr. Young: It was put there to fulfil the function of keeping certain of the upper harmonics in check, and to brighten and give character to the ‘tap-tone’ and further to reduce what we know as the ‘Simpson-howl.’

Mr. Young offered to refer to a standard book on the ‘sounds of musical instruments,’ and said he would be pleased to give the court an imitation of the ‘Simpson-howl.’

The Chancellor: Please don’t, I think we will imagine it (laughter).

Sir Henry Maddocks then questioned the witness at some length in respect to the offer to buy the bells and the reasons underlying it – if the ringers expected to make money by re-selling at a bigger price – and why he was so suspicious that he could not leave them in the tower where at least they could be chimed.

Mr. Young replied, in effect, that he had thought the Cathedral might require further funds.

The offer might be quixotic, but it was bona fide, and Coventry would have had the bells back at cost. He agreed that the bells might remain in the tower for chiming. He was always pleased that bells should remain in their towers, as all sorts of unfortunate accidents often happened to them when they left it.

The Chancellor: What do you mean?

Mr. Young: well they might get cracked, or otherwise injured in lowering, or in their long journey to and from London.

Sir Henry: You would rather they went to Taylors?

Mr. Young: Yes, it certainly has the advantage of being nearer.

Sir Henry concluded his cross-examination by saying, ‘Our bells are not for sale.’46,500 RINGERS

Canon G. F. Coleridge, M.A., then gave evidence. He said that he was the President of the Central Council of Church Bell Ringers, and that he had 50 years’ experience of ringing, from the time he was at Oxford until now. He had rung peals of from 5,000 to 15,000 changes. The questions had been asked as to the number of ringers. He was able to state that there were, according to a recent census, 46,500, and all the best of them were in touch with the Central Council. He had always known that the Cathedral Church of St. Michael, at Coventry, was famous for its bells, and that they were compared with two other famous peals, St. Peter Mancroft, Norwich, and Painswick (the old 10). It would be disastrous to tamper with them, and he was sure that if this proposal came before the Council at Whitsun next, it would be rejected in toto.

Questioned by the Chancellor, Canon Coleridge said that he thought the ‘Simpson’ principle might be all right so long as it was confined to town halls and such public buildings, but for St. Michael’s and such towers, nothing should be done to alter the bells.

Sir Henry Maddocks, cross-examining: What principle do you advocate should be adopted in respect of this proposal?

Canon Coleridge: I should put them in as they now are.

Sir Henry: Would you advocate the augmented seventh?

Canon Coleridge: Don’t ask me anything about music, I know nothing of it or augmented sevenths.

Sir Henry: You, as President of the Bell Ringer’s Association, say you know nothing about it?

Canon Coleridge: No, I am not musical, and it is the practical side of ringing that I enjoy.

Sir Henry: What you want is to get a bell with a good swing with it?

Canon Coleridge: Exactly! And one that has got a wheel on it (laughter).

In further reply to the Chancellor, he said that not having a musical ear, it could not be said to make much difference to him personally, whether the bells were in or out of tune.

Mr. F. E. Dawe, in giving evidence, said that he had been a ringer for 50 years, and had rung Coventry bells over 40 years ago.. Examined as to the reputation of the bells, the witness said: There are, of course, in the many peals up and down the country, bells good, bad and indifferent, and there are exceptional cases of one, or, even more rarely, two good bells standing out because of their fine tone. There was, for example, Bow tenor, the 11th at Southwark, the old 9th at Exeter.

Sir Henry, intervening, said he protested against irrelevant statements, and asked that the witness should confine himself to the question on Coventry bells.

In reply to the Chancellor, Mr. Dawe said that he was going to say that all the bells at Coventry were exceptionally fine, absolutely perfect.

Cross-examined by Sir Henry, witness was asked as to his manner of testing or coming to an expert decision in regard to a peal. He said that he disagreed with the experts on both sides (laughter), as he did not think the tests fair to the bells, the latter should be allowed to speak for themselves. Asked further as to whether his memory could be relied on after so long a period as over 40 years ago, Mr. Dawe replied that all knew that peal conductors necessarily had exceptionally fine memories. His chief objection to ‘Simpson’ tuning was that as a conductor it made his task more difficult, inasmuch as owing to the ‘howl’ he had often to rely on rope-sight, and not upon being able to check the bells coming up at the course-ends by ear. He took great exception to the statement that had been made that ringers had not good ‘ears,’ the exact contrary being the case.

A FINE PEAL OF HISTORIC INTEREST

The Rev. H. H. Drake, secretary of the Suffolk Guild, said that his Guild of 500 members were, as a body, opposed to the scheme. He was not an opponent of ‘Simpson’ tuning, his point being that it was wrong to destroy old peals simply because they were not on that principle. St. Michael’s, Coventry, bells were not only a fine peal, but were of the greatest interest historically. If we thus went on destroying peals we should have no record left of the fine craftsmanship of the old founders.

Mr. T. Miller, of Birmingham, stated that he had had 50 years’ experience as a ringer. By trade he was a bell-tuner. He was one of the few left who had rung upon these bells, having rung there as many as eight times, he thought. Ringers would often rather listen than ring. He and everybody knew them to be a very fine peal. Their notes had a certain quality which he called ‘solid.’

In cross-examination, his attention being called to the series of faults in the bells, as enumerated by the experts, he said if these faults did exist (i.e., that all the bells except the two lower ones were 1/4-tone flat), then it was quite easy to lower those two, so as to bring the whole into line.

The witness was asked several questions by the Chancellor in regard to tuning, and ‘Simpson’ tuning in particular. Mr. Miller referred to his retuning work on the Lichfield Cathedral bells, for which he got a special testimonial. As regards ‘Simpson’ bells, he did not like them, they had a peculiar quality, inasmuch as their main tones lacked solidity, and their harmonics were nearly always ‘shivery.’

Mr. J. George, of Birmingham, in giving evidence, said that he was a ringer of 50 years’ standing. He had rung in 300 towers, including St. Michael’s, Coventry. He had never come across a finer peal of bells, and it would be unwise to recast them. When he was in the railway service, and travelling to and fro, Coventry was in his district, and taking advantage of this he had on many an occasion spent an hour at Coventry just for the pleasure he found in hearing the bells, though they were only chimed.

Sir Henry: I notice that you appear somewhat deaf; can you hear?

Mr. George: Fairly well.

How long have you been deaf? – 30 years.

Sir Henry: But do you think your hearing good enough to judge bell tones?

Mr. George: Though one ear is deaf, I hear twice as well with the other.

Mr. J. E. Groves, or Birmingham, said that he was a ringer of 40 years’ experience, and was by trade a bell hanger. Though he had not been fortunate enough to have heard Coventry bells in peal, he had often heard the bells chimed. In all his experience he never heard anything better as bells, and he did not think that they could be improved.

THE PETITION GRANTED

Mr. Pritchett then addressed the Court. He said that there was a conflict of evidence as to the necessity of recasting the bells for the purpose of improving them. He thought it would be seen that it was quite possible to keep the present bells and add the new four on similar lines. The bells had historical value as a type of a remarkably good peal of their period, a point to which he lent great emphasis. It was somewhat on a parallel with church plate, etc., two or three centuries old. Eight of the bells had been in existence since 1774, and it was not suggested that they were inefficient, cracked or unusable. They had heard a lot about musical defects, regarding which there was much difference of opinion. He would like to remind the Chancellor, in regard to the properties of the flat seventh, that it was analogous to what they had studied in mathematical problems where a factor was introduced for the purpose of preventing recurrence. He thought the function of the flat seventh hum-note was very probably somewhat similar, inasmuch as it prevented the harmonics getting control of the primary wave lengths of sound. Ringers would gladly see these bells preserved as a fine peal, and he submitted on their behalf that a case had not been made out for the destruction of the identity of the peal, and that the petitioners ought to have time to reconsider it.

Sir Henry Maddocks said that there was common ground for agreement on either side that the bells were not harmonious. It was strange that the only opposition practically was from outside Coventry. The petitioners were quite unanimous, and all they desired was to do their very best for Coventry and its Cathedral bells. Here they had an anonymous generous donor prepared to spend £2,300, whose only impulse was a desire to effect an improvement.

The Chancellor: Can the inscriptions be reproduced on the recast bells?

Sir Henry: Easily.

The Chancellor then reviewed the evidence, and said, a friendly spirit had prevailed throughout. They had had considerable evidence from the ringers, and this had been very helpful, and he felt that from their point of view their intervention was quite justified. He must, however, give due weight to the fact that this was a very generous offer, and that it would appear that the ‘Simpson’ principle would make the peal in tune in every respect. If scientifically they could tune to an octave, why not do it? As to the ‘howling,’ that could not take place until a campanile was built. He had come to the conclusion that to recast the bells was the proper method; they would be having the same metal, and the same inscriptions and the same weight and keynote, the same bells but improved. The faculty would be granted in accordance with the amended petition. There would be no order as to costs.

Reprinted from “THE RINGING WORLD,” January 15th, 1926

Nothing will now save the famous Coventry bells from the fiery ordeal through which they are destined to pass, but a stiff fight was put up by the Central Council last week to save what had been looked upon, not merely for years, but for more than a century as the finest peal of ten bells in England. For this act on the part of the Council, our central body deserves the thanks of the Exercise, and, despite the fact that in this case they were unsuccessful, we hope the Council will continue to keep a watchful eye on all attempts to destroy church bells, hung for their original purpose, in order to provide carillons. Admittedly the position at Coventry was unique. The cathedral was in possession of a peal of bells which could not be utilised for ringing because the tower is not deemed sufficiently stable to carry a ring of bells when in motion, and under present conditions nothing more than chiming is possible. The suggestion that the bells should be recast into a carillon of fourteen – the necessary funds having been offered – was seized upon with avidity by the local authorities, but they have at least had to bow to public opinion in so far as to revise their scheme to provide that the extra bells should come out of new metal, and that the old should be retained at their present weights. So far, so good. They also incorporated in the plans provision for hanging twelve of them for ringing purposes, if and when a suitable tower is provided. That, we are afraid, will not be in the lifetime of any reader of these lines.

These points having been conceded by the petitioners, the battle of the Consistory Court turned on whether there was any need to recast the bells at all, and here the decision went with the theorists against what, we venture to think, was the weight of practical evidence. Dr. Brazil, whose musical knowledge no one questions, but who, as a bell expert, was unknown to anyone in ringing circles, and Professor Starmer, were the two witnesses upon whom the petitioners relied to carry through their scheme, and, to be candid, we do not think the opposition was fully prepared to meet their evidence. For instance, an utterly misleading piano demonstration was given, but these ‘illustrations’ doubtless carried great weight with the Chancellor, as they would with anyone who did not know how really fallacious the comparison is. On a piano one gets a chord of five equal tones, but in a single bell this is not the case. When a bell is struck the fundamental and harmonic tones are not equal – if they were, bells in peal would be unbearable – but the piano illustrations, of course, ignored this all-important fact.

There was one other striking instance in which the case for recasting was put in such a manner that, to say the least, put the present bells in a worse light that they really were. Dr. Brazil said that the front seven bells were each a quarter of a note flat, and he based this statement upon the judgment of his own ear. Actually proved, by instruments, and based upon the note of the tenor, two of the bells were dead correct, and the other five were each out to the extent of only from one to three vibrations per second. So that, after all, Coventry bells, which could have been tuned at the saving of some hundreds of pounds, thus enabling the authorities to install a much larger carillon had they desired it – a point which was, perhaps, overlooked in the eagerness of the ‘Simpson’ enthusiasts – have been condemned not only unheard; but, if one may perpetrate the crime of using such a phrase, on ‘earsay’ evidence alone. What we may hope for in the future is not only that the Central Council will act as energetically in all cases where church bells, hung for ringing, are threatened, as in this case, but that our English founders, upon whose advice church authorities very rightly largely rely, will always throw their weight into the scale for retaining English bells for English bell ringing.