Though much documentation from the Gillett & Johnston bellfoundry in Croydon has been lost, almost all the tuning books survive. The books from 1877 to 1951 are held in Croydon Central Library and can be viewed by appointment. The catalogue entry is here. The archive is located at Katharine St, Croydon CR9 1ET and the archive is open (as of November 2025) on Wednesdays and Fridays.

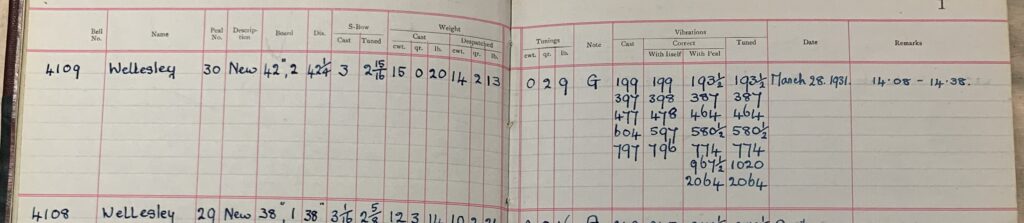

To help in interpreting the entries in the books, here is an example (the bass bell in the carillon at Wellesley, Massachusetts, USA, cast in 1931) and an explanation of each item in the record. I believe the books were written up as a summary of the actual records kept by the bell tuner. Certainly in the few cases where the tuner’s records survive, they provide much more detail about the tuning process. Click on the picture to see a bigger image.

Bell No. – a unique number assigned to each bell cast. This number is generally cast on the crown of the bell or elsewhere.

Name – the name of the town or tower for which the bell was cast.

Peal No. – the number of the bell in the peal or carillon. The heaviest or largest bell has the highest number, even in carillons where the convention is that the bells are numbered from the bass bell as 1.

Description – New (a newly cast bell), Recast (a new bell but a recasting of a previous one) or Old (a bell from another founder being retuned).

Board – the strickles used to make the inner and outer moulds for the bell. In this case, the bell was intended to be 42 inches in diameter. The number refers to a specific strickle of this size.

Dia. – the actual diameter of the bell as cast, in inches.

S-Bow – this is the thickness of the soundbow in inches at the thickest point. Cast is the thickness as cast, Tuned is the thickness after tuning. In this bell, the soundbow thickness was reduced by 1/16 of an inch during tuning.

Weight – all three sets of weights are given in hundredweights, quarters and pounds. Cast is the weight before tuning, Dispatched is the weight after tuning, and Tunings is the weight of metal taken out of the bell. The three sets of figures often don’t add up exactly, as in this case. In early books, for example for the entries for the peal of 12 at St Peter, Wolverhampton, West Midlands cast in 1911, the Cast and Tunings weights are given but the column titled ‘Tuned’ is blank.

Note – the intended note of the bell after tuning.

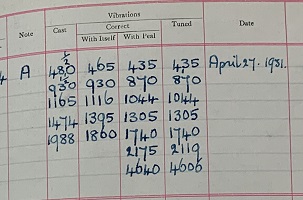

Vibrations – these are frequencies in cycles per second. They were measured using tuning forks – but see my page on anomalies in the tuning forks to see how far out the G&J forks were. The first five frequencies given here are, in order, the hum, prime, tierce, quint and nominal. Where more frequencies are given, generally for larger bells after the mid 1920s, the extra figures are for a partial between nominal and superquint (the high fourth) and partial I7. See here for an explanation of the partial names. The four sets of figures are Cast – those measured before tuning; Correct With Itself – the nearest frequencies to Cast that would give a true-harmonic bell, with hum, prime and nominal in octaves; Correct With Peal – the frequencies required to make the bell true-harmonic and also in tune with the rest of the bells in the peal; Tuned – the frequencies measured after tuning. In this case the bell was almost exactly true-harmonic as it came from the foundry, but had to be tuned down a little to meet the designed frequencies for the whole carillon. Apart from the high fourth, the tuner matched the designed frequencies exactly. The failure to tune the high fourth is not surprising. Cyril Johnston was not aware that the partials above the nominal cannot be tuned independently, they all move together are are determined by the shape of the bell. The very accurate tuning is typical of G&J work, though sadly let down by the errors in the tuning forks.

In some of the tuning book records, a small figure is written above the frequency. I believe this refers to the presence of a doublet on the partial and gives the spacing in cycles, or equivalently the beat frequency in beats per second, between the two doublet frequencies. Here is an explanation of doublets. For a number of bells in the Wellesley carillon with these small figures above a partial, there is a doublet on the partial with approximately the spacing given by the small figure. Here is an example (bell 9 at Wellesley):

As cast, this bell had a ½ Hz beat on the hum and a 1½ Hz beat on the prime. After tuning the book suggests there was a 1 Hz beat on the prime. In my recording of this bell, the prime has a doublet with frequencies 867.6Hz and 868.5Hz.

Date – This is the date that tuning of the bell was completed.

Remarks – I am not aware of the significance of the figures in this column. For most bells this column is blank.

I am grateful to Alan Buswell for his provision of extracts from the tuning books to me and many others over the years, and to Chris Pickford and Kye Leaver for additional information and interpretation.