This paper has been updated with review comments, photographs and suggestions from Paul-Félix Vernimmen, and comments from Michael Loris, and further updated following discovery of the foundry book record for the smallest Philadelphia bell.

The Van Aerschodt family were one of the major bell-founders in Belgium in the second half of the 19th century. André Van Aerschodt (1814 – 1888) and his younger brother Séverin (1819 – 1885) were descended from the van den Gheyns who had been casting bells since the early 1500s. Séverin’s foundry at Leuven was started in 1851, and his son Félix (1870 – 1943) continued the bell-founding business into the 20th century. (ref 4)

Luc Rombouts in Singing Bronze gives details of the Van Aerschodt family and says “Séverin claimed in his prospectuses that he could cast bells with a minor third harmonic and with a major third harmonic . . . Despite this promising claim, it appears that – like his older brother – Séverin had not mastered the tuning technique of the Hemonys or of their own great-grandfather Andreas Jozef Vanden Gheyn”. (ref 6)

André, Severin and Félix cast at least 22 carillons. Unfortunately the musical quality of their bells was often poor, and many of these carillons have been replaced. The big bells cast by the Van Aerschodts are often superb, but that is a matter for another study.

The two carillons by Séverin Van Aerschodt investigated here are Eaton Hall, Cheshire, UK (cast 1877) and Holy Trinity, Philadelphia, USA (cast 1882). Both are of historical interest.

The Eaton Hall carillon is the only surviving Van Aerschodt carillon in the UK. The light carillon of 36 bells at St Botolph, Boston, Lincolnshire cast by André in 1867 was recast by Gillett & Johnston in 1897 into four clock bells (ref 3). This carillon did not have a baton clavier, but rather a Gillett & Bland chiming machine, similar to that at Eaton Hall (ref 5). The 35 bell carillon at St Peter & Paul, Cattistock, Dorset, originally cast by Séverin in 1872 and extended by Félix with two bells in 1899, was destroyed by fire in 1940. The 37 bell carillon of 1885 at St Nicholas, Aberdeen was recast by Gillett & Johnston in 1952. (ref 1)

The carillon at Holy Trinity, Philadelphia was the first carillon to be installed in the USA with a baton clavier. There is a set of 23 bells with a baton clavier at the Basilica of the Sacred Heart, Notre Dame, Indiana cast by Bollée in 1856 but the clavier was only installed in the 1950s (ref 7). There is another carillon cast in 1931 by Félix Van Aerschodt and Michiels at the Cathedral of Our Lady of the Angels, Los Angeles, California. (ref 8)

Both Séverin and Félix originally trained as sculptors. Séverin’s bells are beautifully ornamented and his foundry was also a sculpture foundry. The foundry had a vertical lathe for bell-tuning (documented in a drawing of 1888) (ref 1) and it is clear from the foundry records and from inspection of the bells that they were machined after casting to alter their note. But the tuning records also show that this tuning was done by ear, not by measurement of frequencies. As a result, the nominals of the bells at both Eaton Hall and Philadelphia are only roughly in tune, and the other partials in each bell are not at all in tune.

To show the musical effect of the bells, here is an arrangement of Samuel Wesley’s Gavotte in F performed on the bells at Eaton Hall. As the chiming machine does not operate, this performance is computer-generated, using actual recordings of the bells. Here is a (real!) recording of Lisa Lonie playing the Philadelphia carillon.

The rest of this paper gives more details of the installations at Eaton Hall and Philadelphia, gives examples of the foundry records and information that can be deduced from them, and looks in detail at the tuning figures of the bells.

The photo of Eaton Hall is courtesy of Peter I Vardy and Wikipedia. That of Philadelphia is courtesy of mapio.net.

Eaton Hall

The bells at Eaton Hall are not a carillon in the traditional meaning, as there is no baton clavier. The bells can only be played by a Gillett & Bland chiming machine after Imhof’s patent. This machine plays tunes from pinned barrels. To allow rapid repetition of notes, two hammers are provided for each bell for a total of 56 hammers. The hammers are normally held raised, and drop when triggered by the relevant pin on the barrel. They are raised again by a mechanism independent of the barrel pins. Five barrels are provided with a total of 34 tunes. The chiming machine was restored in 1968 and converted to electric drive. It was not operated on either of my two visits. Because the wires linking the hammers, roller bars and bellcranks are permanently under tension even when the machine is not operating, I should think that constant adjustment would be needed to keep the installation in playing order.

The clock also strikes quarters and the hour on five of the bells. The clock and chimes were working on my visits. The bells are hung dead in the original timber framework.

Rev H R Haweis’ paper on Bells and Belfries (ref 2) on page 386 says “The Duke of Westminster has a fine carillon cast, at my suggestion, for Eaton Hall, by Séverin Van Aerschodt (unhappily since dead), but great pressure having been brought to bear upon the illustrious founder to supply the bells to time it proved beyond his powers to tune them accurately. The suite cast for Cattistock Rectory, again under my direction, by Séverin Van Aerschodt, are in this respect much more satisfactory”.

A paper by Paul Fraser and Steve Thomas documenting a visit made in 2000 gives more many more details and photographs of the clock and chiming machine, and includes correspondence with Alfred Waterhouse (the architect for Eaton Hall), Séverin Van Aerschodt, and John Stainer (who helped with selection of tunes for the barrels).

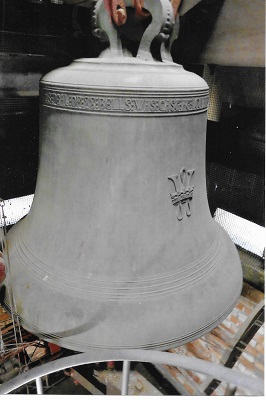

The picture on the left is one of the Eaton Hall bass bells. The elegant W monogram (for Westminster) appears on all the bells. Also visible is part of the inscription, which reads “THIS PEAL OF 28 BELLS WAS CAST AT LOUVAIN FOR HIS GRACE THE DUKE OF WESTMINSTER BY S VAN AERSCHODT A. D. 1877”. The quality of the casting is evident from this photograph. On the right is part of the transmission mechanism, showing the complexity of the links between the chiming machine and the hammers for each bell.

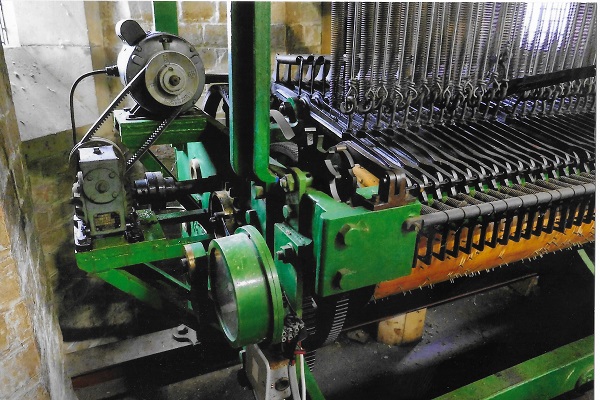

This photograph is of part of the chiming machine, showing part of the pinned drum beneath, the lightweight triggers in front of the drum which are tripped by the pins, and the mechanism allowing the hammers to drop when triggered and then immediately be raised again. One of the levers towards the right of the photo, which is attached to the wire going to the hammer, is up because it has been triggered and not yet restored to its latched position. The electric drive installed in 1968 is visible on the left. All three photos above were taken by Paul-Félix Vernimmen.

Full details of weights, diameters and tuning figures of each bell are here.

Philadephia

The carillon at Holy Trinity, Philadelphia was installed in 1883, a gift of Joseph Temple in memory of his wife Martha Ann Kirtley Temple. The bells were actually cast in 1882. The carillon was installed from the start with a baton clavier, though some bells were electrified by Schulmerich in 1955. The carillon was disused by 1991. It was restored in 2000 by Verdin with new framework, transmission and clavier and re-dedicated in 2001. The bells were not tuned during the restoration.

The pictures above show the remains of the old clavier (in the Verdin museum in Cincinnati) and the new clavier.

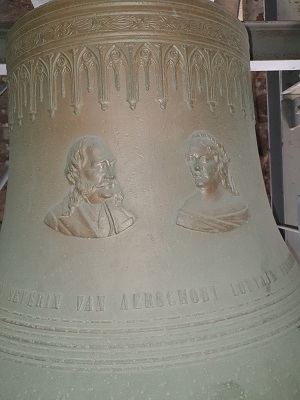

The picture on the left is one of the larger bells, showing the very fine decoration – possibly the donor and his late wife, whose names appear on many of the bells. The picture on the right is the one of the smallest bells in the top tier of the three-tier steel frame, showing again the fine decoration and the clapper mechanism from the Verdin restoration.

Full details of weights, diameters and tuning figures of each bell are here.

Foundry records

The foundry records relating to the casting of these two carillons have been preserved and Paul-Félix Vernimmen kindly provided copies of all the relevant pages. The information in the record for each bell allows us to infer how Séverin Van Aerschodt designed and tuned his bells.

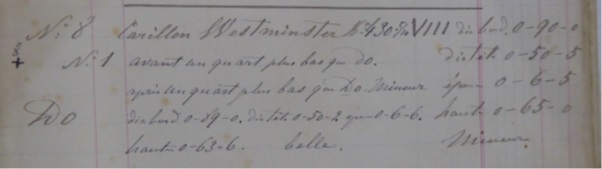

The format of the record for each bell is very similar, both for Eaton Hall and Philadelphia. Each entry was completed in two stages. Here is an example of the initial data entered for each bell:

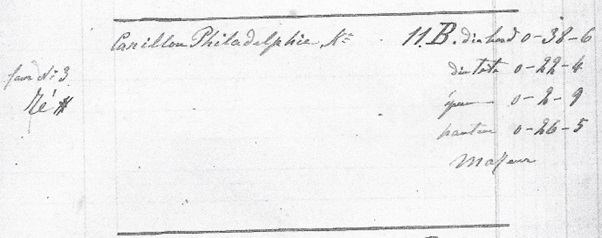

The first line of the entry has the installation or client (Carillon Philadelphie in this case), the abbreviation for Kg but no weight, and a roman numeral, possibly in another hand. The roman numeral (IIB in this case) indicates the profile or strickle used for the bell.

In the left column is a furnace number (four No. 3 in this case) indicating which furnace was used to cast the bell, and the expected note (Ré# in this case). Notes are given in Sol-Fa in the scale of A: Do = A, Do# = A#, Ré = B, Ré# = C, Mi = C# etc. Paul-Félix Vernimmen tells me that the notes are given in ‘vieux ton d’orgue’ – old organ tone.

The right-hand column has the mould or strickle settings. The four dimensions given are:

dia bord = mouth diameter (in metres-centimetres-millimetres)

dia tête = head diameter, i.e. at the shoulder

épaisse = soundbow thickness

hauteur = height.

The final item in the right column (Majeure) suggests the bell was intended to have a major tierce.

Some entries have no other information than this, and for these the assumption is that the cast failed, or the bell came out wrong.

An example of a fully-populated entry for Eaton Hall after casting and tuning is as follows:

The weight (430 5/10Kg) is written into the heading. The bell number in the carillon is entered in the left column (No. 8 in this case). Sometimes the colour of the ink and the handwriting suggests the bell number was written with the initial entry. This bell was cast in furnace No. 1.

In the centre, information is given before (avant) and after (aprés) tuning. The note before is given as “un quart plus bas que Do” – a quarter of a tone lower than Do. The note after is given in the same way, together with mineure (suggesting a minor tierce) and the dimensions after tuning. Examples of descriptions of notes for other bells include “un quart plus haut” – a quarter of a tone above, “un nuance plus bas” – a tiny bit below and “juste” – exact.

Finally, there is almost always a comment on the quality of the finished bell: “belle” – beautiful, “trés belle” – very beautiful, and “passable” – OK. The bass bell for Eaton Hall has the comment “fort belle et surtout qu-elle etait en tierze majeure” – extremely beautiful, especially with the major tierce.

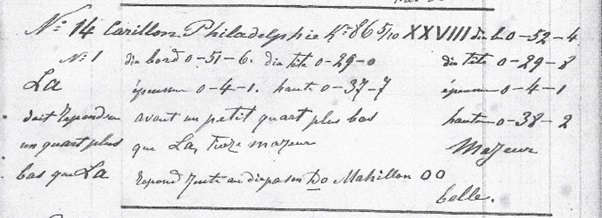

Here is an example of a fully populated entry for Philadelphia:

Paul-Félix Vernimmen provided me with pictures of a couple of strickles and here is the one used to make the mould for this bell:

No note after tuning is given for any of the Philadelphia bells, but at the bottom of the central area we see “repond juste au diapason Do Mahillon” – must be exact to the Mahillon Do tuning fork. Victor-Charles Mahillon was a Belgian musician, researcher in acoustics and instrument maker – an obvious person to supply tuning forks. The text reads like an instruction to the tuner. In the first in the first column we also see “doit repond aux un quart plus bas que La” – must be one quarter-tone lower than La. This presumably uses the same pitch standard as for the Eaton Hall bells.

The notes in the left column do not match the tuning of the bells, they are a semitone out for bells 7 to 25. The notes for the Mahillon forks have the correct sequence of tones and semitones matching the bells as installed. Cross-checking the diameters given in the tuning books against those measured on my visit, and the sequence of notes given for the Mahillon forks, confirms that the numbering of the bells in the tuning book corresponds with the bells in the tower. The Mahillon forks have Do as F, not A.

In many cases, for both Eaton Hall and Philadelphia, the notes after tuning are different from the notes before tuning (and are sometimes different from the design note entered initially). Between the before and after records, notes go up as well as down. So we can infer that Séverin Van Aerschodt knew how to lower the note of a bell (by cutting metal inside the soundbow) or raise it (by cutting the lip). Tuning marks inside the soundbow or on the lip are visible in the Philadelphia bells.

It is also clear from the way the notes are presented, as a difference in quarters of a tone, that the strike notes were being judged by ear against a pitch standard (e.g. a set of tuning forks), rather than by counting beats between partials and the standard. The ‘after’ notes are always a quarter of a tone below the standard, which is explored in the next section.

Here is a photograph of some of Séverin Van Aerschodt’s forks, provided by Paul-Félix Vernimmen. They span from 196Hz to 512Hz in steps of 4Hz, and have threaded tangs for mounting on a resonance box.

There is no reference to any partials other than the tierce. Some bells do have tierces bordering on the major (especially the bass bell at Eaton Hall) but there is not a good correlation between the actual tierce intervals measured, and the descriptions in the tuning books. This justifies André Lehr’s comment about the Van Aerschodts “they were typical 19th century carillon-founders whose romantic ideals about sound obviously overran any concerns for an accurate tone”. (1)

Finally, there is nothing in the foundry records for Eaton Hall to justify the comment by Haweis that the founder wasn’t given time to tune the bells properly. Comments such as “belle” and “trés belle” for almost all the bells suggest Van Aerschodt was happy with his work.

Tuning figures for these bells

It turns out that the bells at Eaton Hall and Philadelphia are very similar in design and tuning, and it is useful to consider them together. In all the charts below, the horizontal axis is the semitone from the Do below the lowest bell, which is A in conventional notation. This allows both carillons to be shown on the same chart, even though the notes of the bass bells are different. The figures for the partials used are those measured on my visits, not derived from the tuning books.

In this section, all intervals are given in cents. A cent is 1/100th of a semitone, so that an octave is 1200 cents. Intervals with a negative cents value are intervals down.

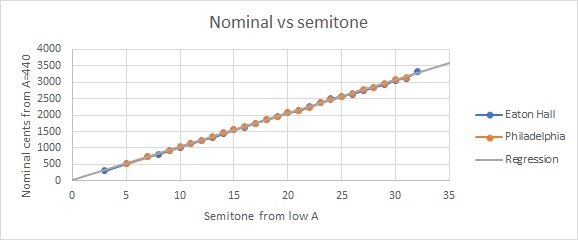

The first question to be addressed is the nominal tuning. Was a temperament used, or are the bells equal tempered? And are the nominals stretched? The first chart below shows the interval of the nominal of each bell relative to A=440Hz:

This chart shows that both carillons are tuned to the same tuning standard. Extrapolating the regression down to the low A gives a frequency for that note of A=444.3Hz. It look as as if the intent was to tune to something close to A=440. In the tuning books, all notes after tuning are given as a quarter of a tone below the pitch standard used. This would give A for the pitch standard as 452Hz. Paul-Félix Vernimmen tells me that the pitch standard used was vieux ton d’orgue – old organ tone. Why Séverin Van Aerschodt tuned his bells to A=440 using a tuning standard using A=452 is not known, but the figures are quite clear. If we assume that Do for the Mahillon forks is F, they also correspond to A=440.

The regression line shows that the bells are stretched by 20 cents per octave. The wide variation in the nominals means that the temperament is not clear, though equal temperament is a reasonable fit.

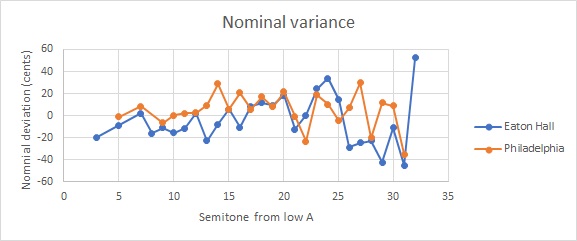

The next chart shows the deviation in cents of each nominal from the 20 cents-per-octave regression line:

Clearly there is a wide variation in the nominals, between 40 cents flat and 40 cents sharp. An alternate version of this analysis was done assuming that hums, not nominals, set the pitch for the top bells, but this did not reduce the variation in the results. The standard deviation of the error in the nominals is 19 cents (this compares with around 11 cents for the historical UK founders studied here). So the nominals are not closely tuned, further confirmation that the tuning was done by ear.

An investigation was done into the nominal variation against octave nominal and prime tuning, as was done in the study of historical UK founders. No significant correlation was found, so the stretch in the nominals is unexplained, unless the tuning standard being used was also stretched.

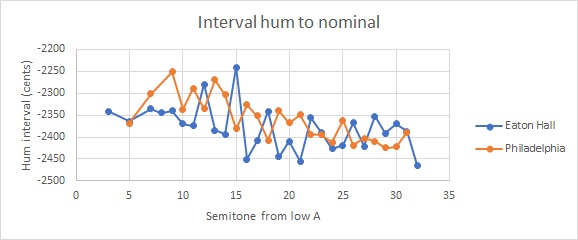

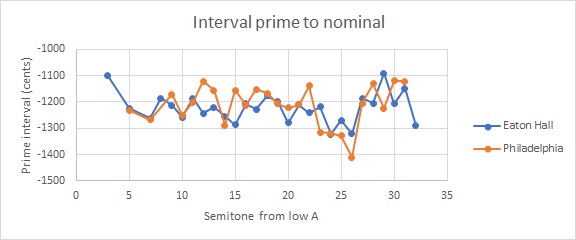

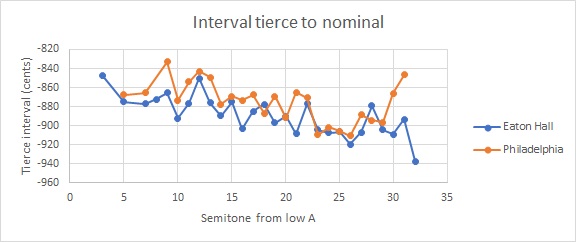

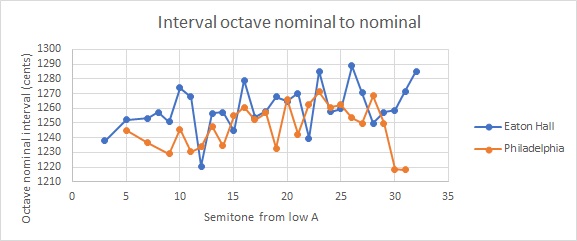

The remaining plots in below show the hum, prime, tierce and octave nominal intervals to the nominal:

True-harmonic tuning would have the hums at -2400 cents and the primes at -1200. Both hums and primes show wide variation – one or two semitones out, with no consistency across the carillons. Some of the tierces are quite sharp, nearer to major than minor, but again with no consistency across the carillons. As Luc Rombouts says (ref 6) and the tuning books also show, Séverin believed that he could produce either minor or major tierce bells, but there is little or no correlation between bells he believed to be major and the actual tierce tuning. Finally, there is a wide variation in octave nominal tuning (which will affect the strike notes) with no gradation between large and small bells.

So unfortunately the poor musical reputation of Van Aerschodt bells is confirmed by these figures, despite individual bells sounding sweet.

Acknowledgements

The visit to Eaton Hall on 6 April 2022 was organised by Chris Pickford and Paul-Félix Vernimmen and I appreciate the invitation to join them. We are all grateful to the Duke of Westminster for allowing the visit and to Nicola Steele, archivist, for hosting us. Nicola provided us with a number of archive documents relating to the installation of the carillon. I had previously visited the carillon on 3 June 2012 on a trip organised by the Central Council of Church Bellringers.

I am grateful to Donald Meineke, Music Director, and Lisa Lonie, carilloneur, for arranging the visit I made to Holy Trinity, Philadelphia on 6 July 2022, and to Lisa for providing information about the bells, especially the restoration in 2000/2001.

Paul-Félix Vernimmen is a grandson of Félix Van Aerschodt and has the foundry books for the period when the Eaton Hall and Philadelphia bells were cast. He kindly provided copies of the relevant pages, and photos of the Eaton Hall installation, tuning forks and strickles.

Carl Scott Zimmerman’s towerbells website provided useful information on several chimes and carillons.

Michael Loris provided helpful review comments on this webpage and pointed out a number of errors in the spelling of names.

References

- Christopher Dalton, The Bells and Belfries of Dorset, Upper Court Press 2000, pp 149-154

- H R Haweis, Bells and Belfries, The English Illustrated Magazine, 1890, pp 380-389

- John R Ketteringham, Lincolnshire Bells & Bellfounders, 2nd edition 2009, pp 37 – 42

- André Lehr, The Art of the Carillon in the Low Countries, Lannoo 1991, p 209

- Thomas North, The Church Bells of the County and City of Lincoln, Leicester 1882, p327

- Luc Rombouts, Singing Bronze, Lipsius Leuven 2014, pp 166-168

- Information on Notre Dame, Indiana from towerbells.org

- Information on the Cathedral of Our Lady of the Angels, Los Angeles, California from towerbells.org